Building the Chiptune Challenge: A Year-Long Music Competition Platform

Building the Chiptune Challenge: A Year-Long Music Competition Platform

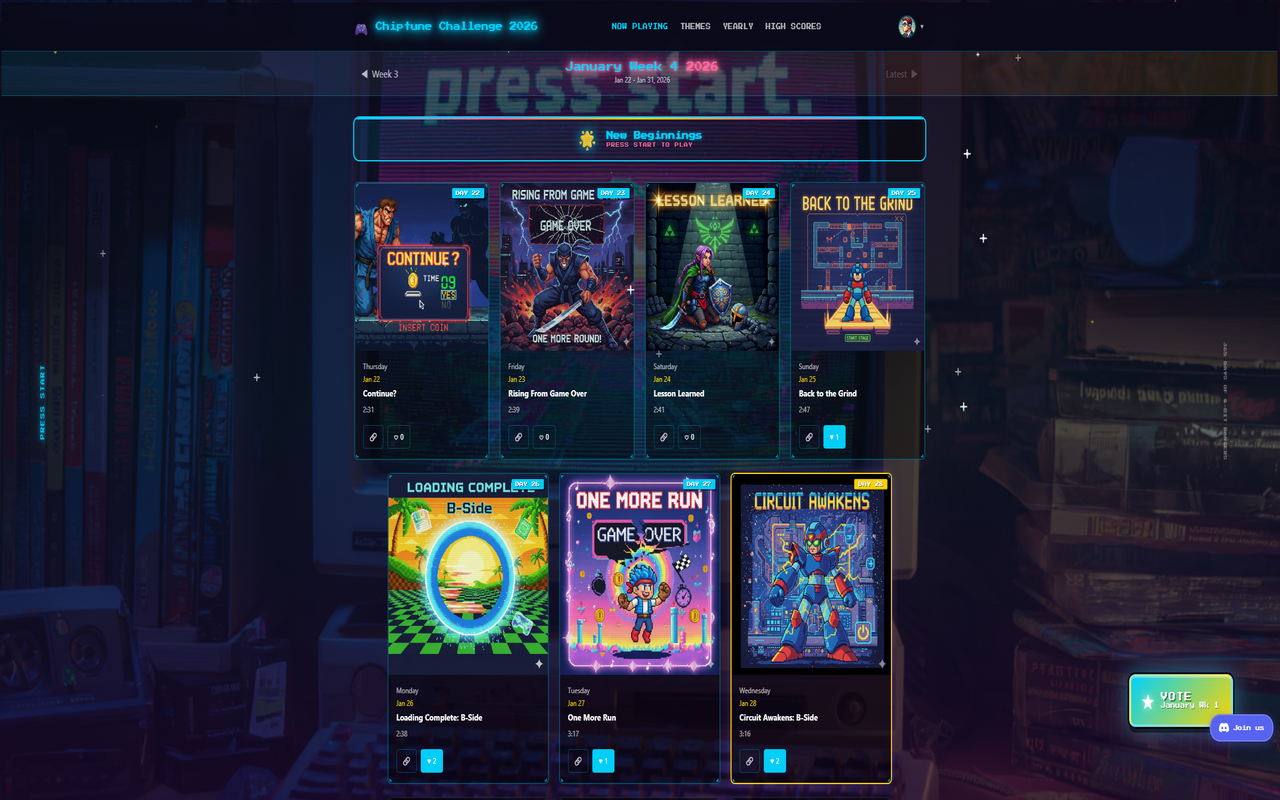

Last weekend, I set out to build something a little different: a platform for an entire year of 8-bit music competition. 365 songs. Weekly voting. Monthly brackets. A yearly championship. All wrapped in a retro aesthetic that changes every month.

The result is the Chiptune Challenge – and it pushed me to solve some genuinely interesting engineering problems. Here’s how it all works under the hood.

What Is the Chiptune Challenge?

The Chiptune Challenge is a year-long competition where a new 8-bit song drops every single day. The community listens, votes on their favorites, and the best songs advance through a multi-tiered tournament system:

- Daily releases – a fresh song every morning at 8 AM Eastern

- Weekly voting – pick your favorite from each week’s batch

- Monthly brackets – the top weekly winners face off in semi-finals and finals

- Yearly championship – the 12 monthly champions (plus wildcard qualifiers) compete for the ultimate title

Think March Madness, but for chiptune music, and it runs all year.

The Competition Structure

The tournament system has three tiers that feed into each other:

Weekly Voting

Each week, listeners vote for their single favorite song. One vote per person, per week. At the end of the voting period, the song with the most votes advances. Ties are broken first by total likes, then by release date (earlier wins).

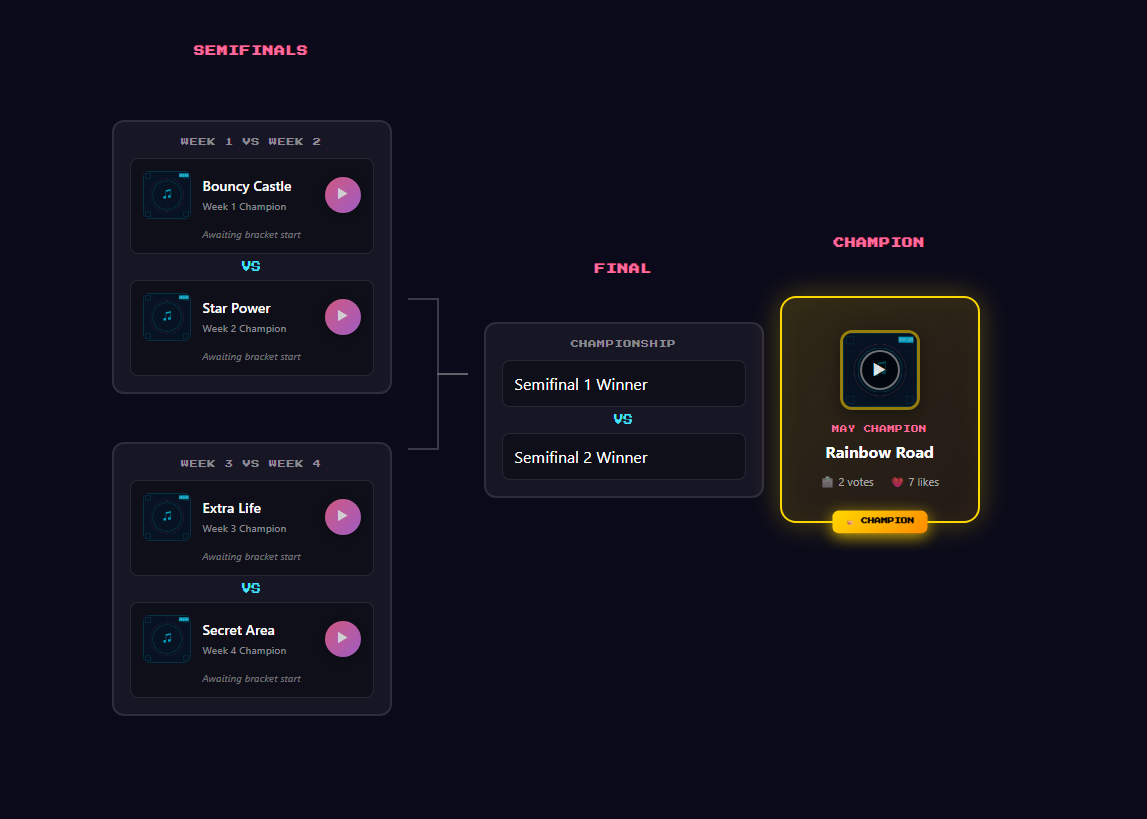

Monthly Brackets

The weekly winners from each month enter a bracket tournament. Two semi-final matchups narrow the field to two songs, then a final determines the monthly champion.

Yearly Championship

This is where it gets interesting. The yearly championship has four distinct phases:

- Wildcard Round – The 12 monthly runner-ups compete for 4 additional spots. Each voter gets up to 4 wildcard votes across all candidates.

- Group Stage – 16 songs are divided into 4 groups (A through D), each containing 3 monthly champions and 1 wildcard qualifier. Voters pick one favorite per group.

- Semi-Finals – Group A’s winner faces Group D’s, and Group B faces Group C.

- Grand Final – The two semi-final winners compete for the yearly title.

This structure ensures that every monthly champion gets a shot at the title while still rewarding the strongest performers from each month.

Technical Architecture

The Chiptune Challenge is built as part of the Zimventures multi-tenant Django platform. Here are the key technical decisions and how they played out.

Django Backend with Multi-Tenant Routing

The chiptune app lives within a larger multi-tenant Django project. When a request comes in, custom middleware identifies the tenant by domain and routes it to the appropriate URL configuration. The chiptune feature sits behind /chiptune/ within the Zimventures tenant.

This architecture means the chiptune app shares authentication, static file serving, and admin infrastructure with all the other sites on the platform – no separate deployment or database needed.

Discord OAuth Authentication

Since the Chiptune Challenge targets a community that already lives on Discord, it made sense to use Discord as the sole authentication provider. The OAuth flow works like this:

- User clicks “Sign in with Discord”

- The server generates a CSRF-protected state token and redirects to Discord’s authorization page

- Discord redirects back with an authorization code

- The server exchanges the code for an access token, fetches the user’s profile, and creates or updates a

ChiptuneVoterrecord - The voter’s ID is stored in the session, bound to their IP hash

That last point is a deliberate security choice. The session is bound to a SHA-256 hash of the user’s IP address (salted), and sessions expire after 24 hours. This prevents session hijacking – if someone steals a session cookie, it won’t work from a different IP. Open redirect attacks are blocked by validating the callback URL against allowed hosts.

HTMX for SPA-Like Navigation

One of the bigger architectural decisions was choosing HTMX + server-rendered HTML over a JavaScript SPA framework. The reasoning was straightforward:

- Simpler mental model – views return HTML, not JSON. No API serialization layer, no client-side state management, no build step.

- SEO-friendly by default – every page is a full HTML document. Search engines see real content.

- Progressive enhancement – the site works without JavaScript. HTMX adds the smooth navigation on top.

In practice, HTMX handles page transitions by swapping content via AJAX requests. The server detects HTMX requests and returns partial HTML (just the page content) instead of the full page shell. Navigation feels instant while the audio player continues playing uninterrupted.

The tricky part was keeping the audio player alive across navigations. Since HTMX swaps only the main content area, the player element persists in the DOM. But the playlist needs rebuilding after each swap, because the song cards on the page have changed. The player listens for htmx:afterSwap events and reconstructs the playlist from the new DOM, maintaining the current playback position.

Alpine.js Audio Player

The audio player is the most JavaScript-heavy component, and Alpine.js was a great fit for it. The player manages:

- Playback state – current song, play/pause, time tracking, volume

- Playlist navigation – built dynamically from song cards on the page

- Keyboard shortcuts – Space for play/pause, arrow keys for seeking and volume, Shift+arrows for prev/next, M for mute

- Drag interactions – both the progress bar and volume slider support click-to-seek and drag-to-scrub, including touch events for mobile

- Persistent volume – saved to

localStorageso it’s remembered across sessions

When a user clicks a song card, the player fetches metadata from an API endpoint and starts streaming. The browser’s <audio> element handles the actual audio decoding – no custom audio processing needed.

One subtle UX detail: if you’re more than 3 seconds into a song and hit “previous,” it restarts the current song instead of jumping back. This matches the behavior most people expect from music players.

Atomic Vote Operations

Voting integrity is critical for a competition. Every vote operation uses Django’s F() expressions for atomic counter updates:

ChiptuneSong.objects.filter(pk=song.pk).update(

week_vote_count=F('week_vote_count') + 1

)

This avoids race conditions where two simultaneous votes could read the same count, both increment it, and write back a value that’s only +1 instead of +2. The F() expression translates to a single SQL UPDATE ... SET count = count + 1 – the database handles the atomicity.

Vote records themselves use unique_together constraints to enforce the one-vote-per-period rule at the database level. Even if someone manages to send two vote requests simultaneously, the database constraint prevents double-voting.

Rate Limiting

All API endpoints are rate-limited using django-ratelimit. The limits are tuned to allow normal usage while blocking automated abuse:

- Song likes: 30 requests per minute

- Weekly/monthly/bracket votes: 20 requests per minute

- Player state requests: 60 requests per minute

These limits are per-IP, so a misbehaving client can’t impact the service for others.

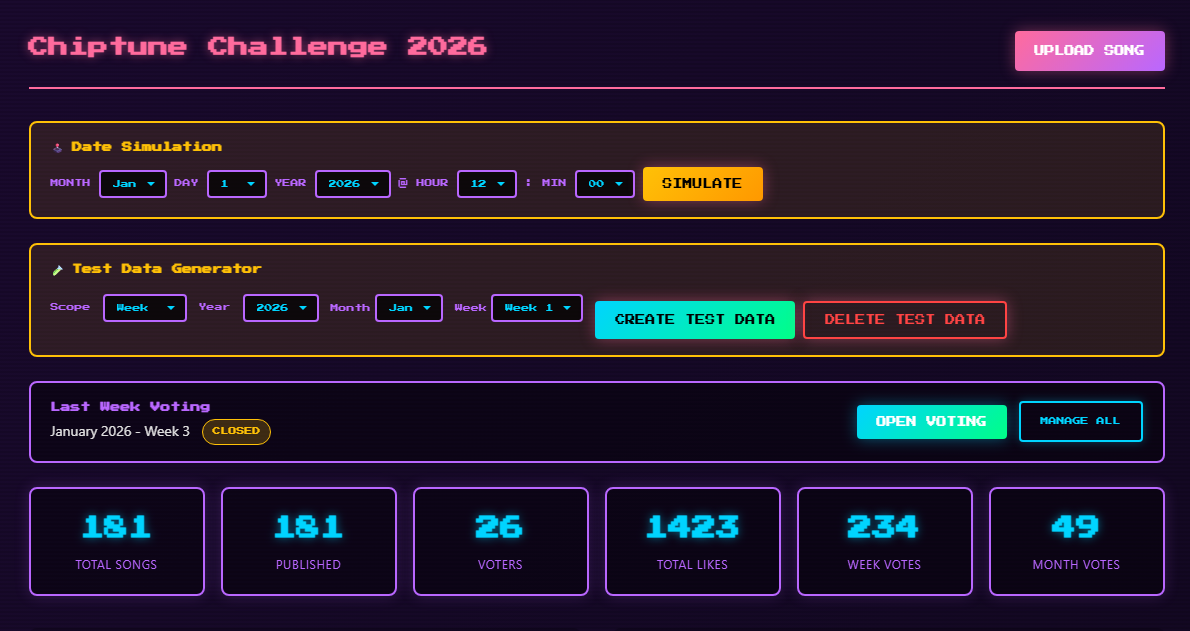

Time-Travel Debug Mode

Development and testing posed an interesting challenge: how do you test a system built around calendar dates without waiting for those dates to arrive?

The solution is a debug settings singleton (ChiptuneDebugSettings) that lets me override the current date. When active, every call to get_effective_now() returns the simulated date instead of the real one. This makes it possible to:

- Test weekly voting transitions

- Verify monthly bracket creation

- Preview future themes

- Validate the yearly championship flow

It’s a toggle in the Django admin – flip it on, set a date, and the entire app thinks it’s that day.

Song Publication Timing

Songs become visible at 8 AM Eastern time each day. The get_effective_date() utility handles timezone conversion:

PUBLISH_HOUR = 8

PUBLISH_TIMEZONE = 'America/New_York'

Before 8 AM ET, the system reports the previous day’s date as “effective,” so tomorrow’s song never leaks early. This works correctly across daylight saving time transitions thanks to Python’s zoneinfo module.

Month-Relative Weeks

Standard ISO week numbers don’t align with months, which creates confusing situations for a month-based competition. Instead, the Chiptune Challenge uses a custom week system relative to each month:

- Week 1: Days 1-7

- Week 2: Days 8-14

- Week 3: Days 15-21

- Week 4: Days 22 through end of month (7-10 days depending on the month)

Week 4 is intentionally longer to absorb the variable tail end of each month. This keeps the competition structure clean – exactly 4 voting periods per month, every month.

The Monthly Theme System

Each month has a unique visual identity that transforms the entire site. The 12 themes are:

| Month | Theme | Tagline |

|---|---|---|

| January | New Beginnings | Press Start to Play |

| February | Arcade Valentine | Insert Heart to Continue |

| March | Adventure Awaits | The Quest Begins |

| April | Pixel Rain | Storms & Synthwaves |

| May | Platform Paradise | Jump Into Action |

| June | Turbo Mode | Maximum Velocity |

| July | Bullet Heaven | Dodge & Destroy |

| August | Chillwave Coast | Sunset Sessions |

| September | Mind Games | Think Fast |

| October | Ghost Mode | Fear the Pixels |

| November | Epic Quest | Level Up |

| December | Victory Lap | Game Complete |

Each theme defines a primary color, secondary color, accent color, icon, and descriptive vibe text. The CSS uses custom properties (--chiptune-accent, etc.) that update when the theme changes, so the entire color scheme shifts with a single source of truth.

The theme system also tracks status – past months show their final results, the current month is active, and future months are locked. This builds anticipation and gives the site a sense of progression throughout the year.

Design Decisions

Why HTMX + Alpine Over a SPA Framework?

The Chiptune Challenge could have been a React or Vue app. But the content is fundamentally page-based – lists of songs, voting forms, bracket displays. Server-rendered HTML is the natural fit. HTMX adds the interactivity (smooth transitions, inline voting) without the complexity of client-side routing, state management, or a build pipeline.

The one exception is the audio player, which genuinely needs client-side state. Alpine.js handles this elegantly – it’s a single component with local state, not a global store. The rest of the app is plain Django templates.

Why Discord OAuth?

The target audience already has Discord accounts. Adding email/password registration would create friction and require building password reset flows, email verification, and account management – all solved problems, but unnecessary overhead when the community is already on Discord.

Discord OAuth also provides avatar URLs and display names for free, making the user profile zero-effort for both the developer and the user.

Why Denormalized Vote Counts?

Every song stores its own like_count, week_vote_count, month_vote_count, and year_vote_count directly on the model. This is deliberate denormalization – the canonical data lives in the vote records, but counting them on every page load would be expensive.

The tradeoff is that vote counts must be updated atomically whenever a vote is cast. Django’s F() expressions make this safe and efficient. The alternative – a COUNT() query joining vote records for every song on every page – would be far more expensive at read time, and reads vastly outnumber writes in this system.

Try It Out

The Chiptune Challenge is live now. Check it out at /chiptune/ – there’s a new song every day, and you can vote for your favorites by signing in with Discord.

If you’re interested in building something like this for your own community or business, I’d love to chat. Visit /services/ or get in touch to discuss your project.

The Chiptune Challenge is built with Django, HTMX, Alpine.js, and a lot of 8-bit enthusiasm.